It was an unusual day in Isla Vista, Calif. The year was 1970, and a loud, energetic man with wild red hair was hawking pens and pencils on the sidewalk. Behind him, a single copy machine sat under the awning of an old hamburger stand.

The man was there that day because he saw an opportunity. Undergrads at UC-Santa Barbara were lining up in the library to photocopy articles for 10 cents a pop. “I could do better,” he thought. So he took out a $5,000 loan and opened his first copy shop.

That copy shop would become the first Kinko’s, the office-supply giant bought by FedEx for $2.4 billion in 2003. The man on the sidewalk, Paul Orfalea, was about to change the way we think about printing. He was also dyslexic. In other words, a dyslexic founded a business that specialized in duplicating reading material.

Under Orfalea’s leadership, Kinko’s became an international juggernaut with 1,200 locations in 10 countries, more than 20,000 coworkers (Kinko’s never had “employees”) and $2 billion in annual revenue. What was the secret behind this explosive growth? Dyslexia, which Orfalea called “a blessing.”

Orfalea’s story is more typical than you might think. In fact, a surprising number of entrepreneurs are dyslexic: Richard Branson, Charles Schwab, Barbara Corcoran, Daymond John, John Chambers, Ingvar Kamprad. And this is only the short list. A study of self-made millionaires in the U.K. found that 40 percent were dyslexic. Former Cisco CEO Chambers estimates that “25 percent of CEOs are dyslexic, but many don’t want to talk about it.”

For years, I didn’t want to talk about it either. I landed my first client when I was 19 years old. I was meeting with the dean of my college when the phone rang. The receptionist said there was someone looking for a graphic designer. The man on the other end of the phone needed a hand branding the Toyota Grand Prix of Miami. I said, “I’ll do it.” I ended up helping him design merchandise for the event — umbrellas, polo shirts, baseball caps. After the race, he came back beaming, “We sold it all!” So I asked, “What else are you selling? Let’s do more.”

For the next few years, I was his go-to guy for the Grand Prix. Then I got other jobs. I kept hustling. Before you knew it, I had more work than I could handle — and I was still a sophomore in college. By the time I graduated, I was already doing projects on the West Coast. That year, I moved to San Francisco and founded Gershoni Creative.

When I hear the early life stories of dyslexic entrepreneurs, I hear my own story. Trouble in the classroom is a universal experience. Investor Charles Schwab flunked English in college. Orfalea failed two grades and was expelled from multiple schools. Discouraging teachers are another familiar roadblock. As Virgin Group founder Richard Branson left school, the headmaster predicted he was “either going to be a millionaire or going to jail.” British entrepreneur Sharon Hewitt was told by her teacher “if (she) worked really hard (she) might be able to get a job as a shop assistant.” Hewitt went on to found an award-winning employee-relocation business.

While dyslexia is often seen as an impediment, its impact on the business world is undeniable. From IKEA to FUBU, dyslexia is a driving force in the modern economy. But what makes dyslexics such successful entrepreneurs?

After reviewing a combination of academic studies and the stories of dyslexic business leaders, five key advantages emerged. I have arranged these strengths into a helpful acronym: DOMES. To be clear, this acronym is not meant to replace scholarly inquiry. I’ve combined my own experiences and observations with some of the more unheralded insights from prominent dyslexic entrepreneurs. By articulating these hyper-abilities — perceived weaknesses that are actually extraordinary strengths — in fresh language, I hope to show that the skills that dyslexia enhances are the same ones that propel dyslexic entrepreneurs to greatness.

D: Delegation

Dyslexics feel comfortable delegating. If you know where your weaknesses are, you’re perfectly positioned to build a team around you that helps compensate for your blind spots. Orfalea confessed there wasn’t a single machine at Kinko’s he could operate. Unable to approach the business from a mechanical point of view, he hired coworkers to fill the operational gaps. He brought in strong oral communicators and relied on his team for written correspondence. Recognizing this need in my own work allows me to relate to my team as a collaborator rather than micro-manager. Delegation is the difference between being a manager and being a leader. Delegation helps dyslexics lead.

O: Oral Communication

Because writing does not come easily to most dyslexics, we are forced to find other ways to communicate. Dyslexic entrepreneurs often hyper-develop their oral communication skills in order to compensate. Branson explained how dyslexia helped him purify his company’s communication. “I need things to be simple,” he said. “Therefore when we launch a financial service company or a bank, we do not use jargon. Everything is very clear-cut, very simple. I think people have an affinity to the Virgin brand because we don’t talk above them or talk down to them.” Dyslexia pushed Branson to simplify Virgin’s voice to clear, powerful language.

M: Mental Visioning

Mental visioning is the capacity to discover nonlinear relationships, to connect dots that others can’t even see. Schwab described how dyslexia “leads to a better visualization capability, conceptual vision,” which helped him outpace and out-imagine his business rivals. Dyslexics are capable of visualizing complicated abstract concepts like business models or advertising campaigns without ever putting pen to paper. “Like dyslexic musicians who say they can see the notes that they’re playing,” says FUBU founder Daymond John, “I can see a business unfolding in my head.” The same behavior that’s maligned as daydreaming in students is praised as innovation as an adult. With some practice, dyslexics learn when to bring others into the play, then work backward to help them access their galactic vision.

E: Emotional Intuition

Many dyslexics possess an emotional intelligence that allows them to attune themselves to people’s hidden ambitions and build trusting relationships quickly. “Dyslexia teaches you how to get people on your side for reasons other than you’re smart,” explains real-estate mogul Barbara Corcoran. “Because as a kid you knew what it felt like to be a loser, you develop great empathy. When I was building my business, I could walk through a sales floor with 150 brokers and if somebody was in pain, I could feel it. I’d go up and say, ‘How are you doing?’” This ability to intuit people’s emotions — whether my clients’ or my team’s — is the foundation of my agency. A client might say they want a new logo, but their body language or tone of voice tells me they need something different, something more. My capacity to identify these underlying signals is how I help companies communicate an authentic version of themselves.

S: Speed

The dyslexic mind is always spinning. When you spin, you’re able to see multiple perspectives in the blink of an eye. You see through things, around things, above things, below things, within things. In this whirlwind, you encounter ideas no one else would find. Chambers described this mental process this way: “You don’t go A, B, C, D, E . . . to Z. I go A, B … Z with speed.” I would add that the dyslexic mind never fires the same way twice. One day it is A, B, Z, C and the next it’s Z, Y, A, G. This nonlinear way of thinking is the essence of entrepreneurship. If you follow the status quo, the prescribed route, a linear progression of thought, it’s a straight line to redundancy and stale ideas.

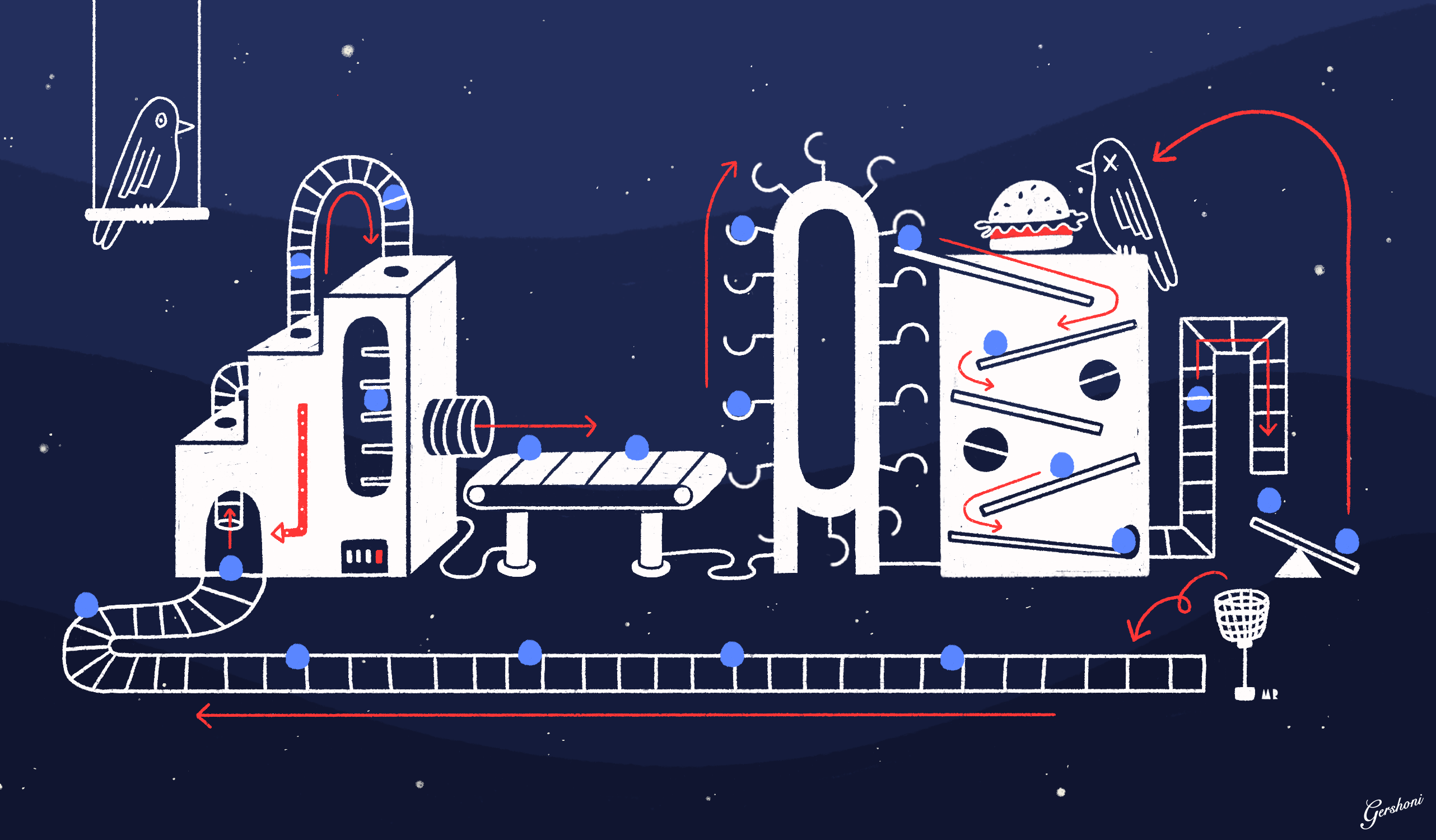

These five abilities help dyslexics achieve success beyond expectation. While most employees fit snugly into a familiar set of roles and responsibilities, dyslexics know that the systems that work for other people will not necessarily work for them. They must invent their own machine.

When I create a set of conditions that fits the way my mind works, the possibilities are endless. The drive to establish new frameworks, and the ideas that spring from it, is where entrepreneurship is born. To be an entrepreneur, you have to look beyond what is accepted and see opportunities where others least expect it. Even in an old hamburger stand.